Chapter Twenty-three

The sounds Mr. Barbicane made were not restricted to his dream. They escaped into the real world as he slept in his bed in the room at the Hyatt Regency hotel at Pittsburgh International Airport. His moan and his groan were startlingly load and while they were not loud enough to wake Mr. Barbicane they were loud enough to be heard through the wall to which the headboard of his bed was bolted.

The sounds of Mr. Barbicane’s distress were heard in the room next to him by a thirty-six-year old man named Lloyd Barton, an engineer for Rocketdyne Corporation, a major NASA contractor and at one time a company owned by the Boeing Corporation, builders of the MD-87 aircraft that had transported Mr. Barbicane from Burbank to Pittsburgh. Rocketdyne is no longer part of the Boeing family, having been acquired in 2005 by United Technologies Corporation where it was combined with the Pratt & Whitney Space Propulsion Division, the resulting corporate entity to be known as Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne.

Mr. Barton was not asleep at the time, but was sitting up in bed going over the specifications of a new dual-mode scramjet which allows an engine to function as a subsonic combustion ramjet at low supersonic speeds, say between Mach 3 and Mach 5, and as a supersonic combustion ramjet at high supersonic speeds, those speeds greater than Mach 5.

To Mr. Barton, Mr. Barbicane’s sounds did not sound like the sounds of someone in emotional pain. Mr. Barton mistook the sounds for the sounds of pleasure and assumed someone was having sexual intercourse in the room next to his.

He set down his papers and turned his head slightly, angling his ear to the wall to hear any subsequent sounds. There were none forthcoming. He sat there. Listening. Poised.

Mr. Barton imagined sex was taking place behind his back. He imagined a man and woman on the other side of the wall. And as he waited to hear more audible evidence of their activities he imagined who they were and how they got there.

He imagined a male traveler, not unlike himself, in the bar of the hotel, just off the lobby. He has returned from an afternoon and evening of meetings. He had dinner with co-workers but is too wound up from the day’s activities to simply go up to his room, so he has stopped at the bar for a cocktail, something to help him unwind.

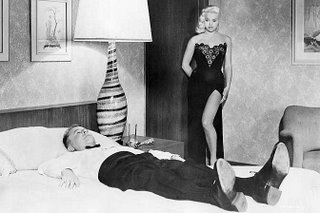

He orders a drink and looks along the length of the bar and sees an astonishing woman. She is tall and voluptuous in a way that makes the man think of movie starlets from the 1960s. Her hair is a cascade of platinum. She wears a scandalously short canary yellow dress with a halter top that barely covers her prodigious breasts and reveals her arms and shoulders and most of her back. The dress is crocheted and there are glimpses of the woman’s flesh through the gaps in the pattern. She is wearing make-up worthy of a showgirl and sips a green martini through a straw to protect her carmine lips. In the dim bar the woman seems to give off light, a sort of sexual bioluminescence. She sits provocatively on a stool, her long legs deliberately crossed, her feet in yellow high-heel pumps the color of her dress.

This is not the sort of creature you see in the bar of the average Hyatt. She is breathtaking in her ability to embody so many male fantasies in one dramatically curved form.

The man is drawn to her. They speak. He buys her a drink. Even though he knows it’s against local law, Mr. Barton imagines the man lighting a cigarette for the woman. She takes the smoke deep into her and slowly releases it as though whistling it away through her moist lips.

Mr. Barton leans his head against the wall behind his bed and imagines the man and woman leaving the bar together. The man puts his arm around her waist and draws the woman against him. She presses her hip against his as they move to the elevator. He pushes the call button, she looks at herself in the mirror between the elevators and inspects her perfection.

The elevator comes. They step into the car and the doors close after them. They are the only ones on the elevator as it rises up into the hotel. She leans against the wall opposite the man so he can see her. He looks at her and as he looks at her she seems to change. Her hips grow more pronounced and her breasts appear to grow, straining against the canary yellow fabric and she makes a small moaning sound as if these changes bring her pleasure. Mr. Barton imagines these changes are linked directly to the desire of the businessman.

The elevator stops at the floor where Mr. Barton and Mr. Barbicane are staying and the two people get out and start down the hallway, past the sconces spaced for perfect illumination. He tells her to walk ahead of him, he wants to watch her ass. She smiles and steps ahead of him, rolling her hips as she walks. She feels his eyes on her and runs her hands along her contours for his enjoyment.

They reach the room next to Mr. Barton’s. The man opens the door for the woman and they step inside. The man turns on one light and stretches out on the bed. The woman stands at the foot of the bed in her canary yellow dress.

He asks her to walk back and forth at the foot of the bed. She does so, pacing back and forth, moving her hands along her breasts and hips and ass as she does so. She does this for quite sometime, apparently never tiring of putting herself on display in this fashion. Then the man swings his legs over the side of the bed and tells her to come to him. She does.

The woman kneels in front of the man and arches her back to present herself to him like some sort of exotic bird.. The man reaches forward and places an open hand on each of the woman’s breasts, pressing gently. The woman makes a purring, groaning sound that one might consider to be a disproportionate amount of response to the pleasure possibly derived from this touch, but it isn’t. Her head goes back, she closes her eyes and her lips part. She is lost in ecstasy and nothing moves for a moment. Then she lowers her head and opens her eyes, her carefully made-up eyes, and looks at the man with a combination of challenge and invitation. Then she reaches for the belt on the man’s trousers.

All this Mr. Barton imagines as prelude to the brief sounds he misinterpreted coming from Mr. Barbicane’s room. And all the while he is imagining these things, Mr. Barton projects himself into the extrapolated scenario. But, it must be noted, Mr. Barton imagined himself not as the businessman, but as the woman in the yellow dress.

Because throughout his life, ever since a crystallizing childhood moment in front of a television set watching an old movie, Lloyd Barton, a man who has helped peel back the outer layers of heaven itself, has had but one profound wish: To be Irma La Douce. To be the sort of woman who populates the full page cartoons of mid-sixties issues of “Playboy.” Mr. Barton dreams of being voluptuous.

He presses the side of his head against the wall separating him from the room of the now peacefully sleeping Mr. Barbicane and listens. He listens and dreams of being long of leg and ample of breast. Someone who in the morning will walk into the pre-dawn grayness with five hundred dollars cash for her work.

Mr. Barton has told no one of his desire to be transformed. And he never will. He will guard it as closely as Vickie will forever hold the secrets of her dream and for many of the same reasons.

Perhaps the fantasy is worse than the act. It’s certainly harder to control. You can stop yourself from taking action, that’s easy. But how do you stop yourself from dreaming?

Mr. Barton touches the wall with his fingertips and closes his eyes.

In Farmers Branch, Vickie opens her eyes to see that the storm has cleared and the moon has come out, full and blue. Her room is filled with moonlight. Dangerous moonlight.

If Vickie knew of Mr. Barton and his dream she might have told him to look for the stream where Salmacis embraced Hermaphroditus and how the water had been cursed in a way to make the engineer’s dream come true.

If man he entered, he may rise again

Supple, unsinewed, and but half a man!

But Vickie knew nothing of Lloyd Barton and he knew nothing of her.

Tired of waiting, Mr. Barton finally gave up the hope of hearing more sex from Mr. Barbicane’s room. He put his paperwork aside, turned out the light and stretched out under the covers and thought about what it would be like to be desired.

As Mr. Barton considered this, Vickie looked up through the dormer window of her bedroom and thought about a poem Ovid didn’t write.

I see the moon,

The Moon sees me

God bless the moon,

And God bless me.